Robert Taylor is Jake Wade, a one-time outlaw turned respected sheriff who decides to pay back a long-ago favor.

Robert Taylor is Jake Wade, a one-time outlaw turned respected sheriff who decides to pay back a long-ago favor.

He breaks condemned killer Clint Hollister out of prison, saving him from a date with a hangman’s noose.

Only problem is, when Wade went straight years earlier after thinking he killed a young boy in a bank holdup, he rode off with $20,000 of loot and buried it.

Now free of jail, Hollister wants that money; only Wade knows where it is.

So Hollister and his men track down Wade to the town where he’s marshal. They also kidnap his lady love (Patricia Owens as Peggy), figuring Wade’s more likely to be in a cooperative mood if she’s in danger as well.

Wade knows the situation is desperate. Once the gang gets the money, it’s unlikely they’ll let he and Peggy escape with their lives.

But before long, everyone’s going to be in danger.

The Comanche are on the warpath. And that loot is hidden in a ghost town in the middle of Indian territory.

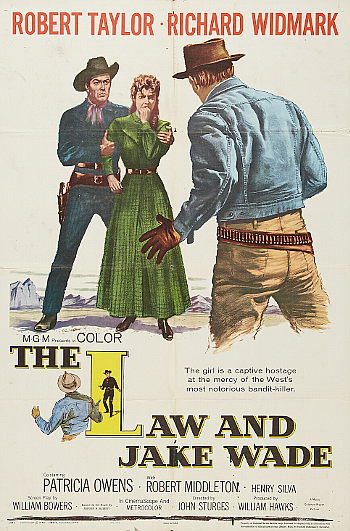

Richard Widmark as Clint Hollister, determined to even the score with a former friend in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

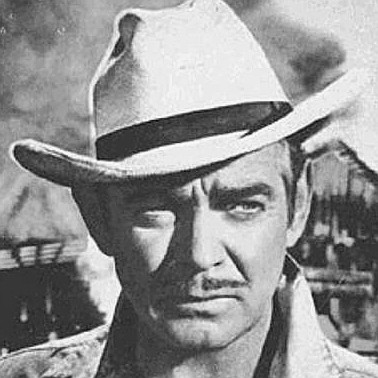

Robert Taylor as Jake Wade, who helps a former friend escape prison and comes to regret it in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

Once you get past that ridiculous opening premise — that a respected lawman would break a condemned killer out of jail, let alone one he owed lots of money — this become a neat little film, with the tension building as Widmark and his gang ride off with Taylor and Owen as their hostages.

The fact that the money was buried in what is now a ghost town in the middle of Indian territory helps heighten the suspense. Suddenly, it’s not only Taylor and his lady love who are facing a life-and-death situation. And it all leads up to a well-done ending.

Widmark steals the show as the wise-cracking badman headed for an inevitable showdown with Taylor.

A year later, Patricia Owen played in another top-notch Western, “These Thousand Hills.” But she’s best known as the wife of the scientist whose experiment goes awry in “The Fly.”

This also marked one of the first roles for Henry Silva, who plays a pastor’s son gone bad, a young hotshot who wouldn’t mind getting his hands on Peggy.

Henry Silva as Rennie, a hot-headed young gun who joins Hollister’s gang in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

Directed by:

John Sturges

Cast:

Robert Taylor … Jake Wade

Richard Widmark … Clint Hollister

Patricia Owens … Peggy

DeForest Kelley … Wexler

Henry Silva … Rennie

Robert Middleton … Ortero

Eddie Firestone … Burke

Burt Douglas … Lieutenant

Runtime: 86 min.

Robert Middleton as Ortero, one of Hollister’s men, finding himself under a gun in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

DeForest Kelly as Wexler, a Hollister gang member with no love lost for Jake Wade in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

Memorable lines

Clint Hollister to Jake Wade: “Just goes to show, no matter how pleasant they are to have around, a woman does slow a man up.”

Rennie, after firing shots that might alert Comanches to the group’s presence: “I didn’t stop to think.”

Hollister: “We’ll chisel that on your tombstone.”

Hollister: “Well, did you say a few words over the boys?”

Ortero: “Yeah, goodbye.”

Hollister: “Very touching.”

Jake: “If things had worked out the way you planned, were you going to give me a gun, or just shoot me in the back?”

Hollister: “Well, that’s an interesting question, Jake. I’d say I was going to give you a gun.”

Jake: “All right.” Then he flings a six-gun into the distance. “There’s your gun.”

Hollister, looking disappointed: “I was going to hand you yours.”

Jake: “Well, you like me a lot better than I like you.”

Richard Widmark as Clint Hollister, free out of jail and wondering where $20,000 in loot is hidden in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

Burt Douglas as the cavalry lieutenant who warns Hollister and his companions of Indian trouble in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

Patricia Owen as Peggy, finding herself a captive of Rennie (Henry Silva) and Burke (Eddie Firestone) in The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

I enjoyed “The Law and Jake Wade” for several reasons. First and foremost, John Sturges helmed this exciting little western. Sturges has a way with orchestrating action scenes. He was doing it long before “The Magnificent Seven” electrified audiences. I’ve read the novel by Marvin H. Albert. Albert would go on to write “Duel at Diablo” and “Rough Night in Jericho.” The scribe on this one was William Bowers, better known for “Support Your Local Sheriff” as well as “The Gunfighter.” The “ridiculous opening premise” was in the novel, too. Actually, I never thought it was as lame as you do. Jake Wade (Robert Taylor) was the kind of tough guy who felt he owed Clint (Richard Widmark) a favor. Call it “honor among thieves.” Sturges stages the opening scene with as unobtrusively as he could, so that Jake wouldn’t be recognized when he slips in and shoves the shotgun into the lawman’s back. However, Clint is anything but unobtrusive. He belts on his gun and clobbers the lawman for serving him “runny eggs” and then without a blink guns down too deputies. The finale at the ghost town is another example of Sturges milking a scene for everything it is worth, including the crescendo orchestrate score. Has anybody ever noticed that the graveyard scene is one of the first to feature stolen loot buried on Boot Hill. If there is an earlier use of this setting, let me know. When everybody thinks about loot buried in a grave, they probably remember Sergio Leone’s “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” Widmark is at his sleazy best, giving us a Tommy Udo performance from “Kiss of Death.” Apart from a couple of scenes lensed on an obvious studio set, “The Law and Jake Wade” was photographed in Death Valley National Park, California, USA and Alabama Hills, Lone Pine, California, USA, Look closely at the scene where Jake and Clint reach their point of departure after the jailbreak. The film cameras that Hollywood used back in those days were extremely bulky and considerable time was probably eaten up transporting that equipment, not to mention the scenes set in Death Valley where Jake tries without success to elude Clint but winds up running smack into him again. Sturges used the landscape with the same finesse and majesty as Anthony Mann. Look at another Sturges western “Joe Kidd” with Clint Eastwood and you can see how he used long shots to frame his riders in their element. Want a scene to complain about? The biggest flaw to me–and I am a Sturges fanatic–is when Jake allows Clint to keep the horse he brought with him. Later, Clint and his henchmen show up in the town where Jake wears a badge. The villains used the horse to track down Jake’s whereabouts. Jake should have known as much when he gave Clint the horse. However, movies are movies, and if Jake had blindfolded the horse, perhaps Clint would never have found him. If that had been the case, there would have been no movie. The other Sturges trademark is the virtually all-male cast with Patricia Owens as the lone female. A lot of familiar faces appear: Henry Silva and DeForest Kelley as a paranoid outlaw with a Southern drawl!